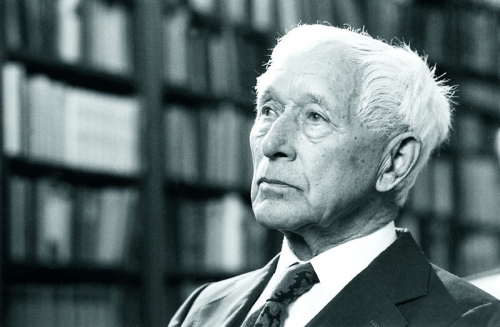

Ernst Jünger und die >Konservative Revolution<.

Überlegungen aus Anlaß der Edition seiner politischen Schriften

Ex: http://www.iaslonline.lmu.de

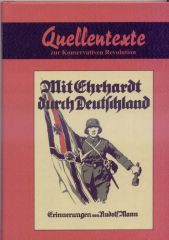

- Ernst Jünger: Politische Publizistik 1919 bis 1933. Herausgegeben, kommentiert und mit einem Nachwort von Sven Olaf Berggötz.

Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta 2001. 898 S. Ln. € 50,-

ISBN 3-608-93550-9.

Das Bild Jüngers nach 1945

Ein gutes Jahr nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtübernahme, im Mai 1934, schrieb Ernst Jünger im Vorwort zu seiner Aufsatzsammlung Blätter und Steine, es seien "nur solche Arbeiten aufgenommen, denen über einen zeitlichen Ansatz hinaus die Eigenschaft der Dauer innewohnt. [...] Aus dem zu Grunde liegenden Material wurden somit die rein politischen Schriften ausgeschieden; – es verhält sich mit solchen Schriften wie mit den Zeitungen, die spätestens einen Tag nach dem Erscheinen und frühestens in hundert Jahren wieder lesbar sind." 1

Drei Jahre nach seinem Tod sind Jüngers politische Schriften nun zum erstenmal wieder zugänglich. Das Bild, das wir heute von Jünger haben, wäre ein anderes, wenn Jüngers Haltung jener Jahre aus diesen Texten bekannt gewesen wäre. Wo Jünger in der Weimarer Republik politisch stand, war bislang nur in Umrissen erkennbar.

Karl Otto Paetel, der von Jüngers regimekritischer Haltung überzeugen wollte, schrieb 1943 in der Emigrantenzeitschrift Deutsche Blätter, "dass sich Ernst Jünger um die Tagespolitik wirklich nie gekümmert" 2 habe. Paetel hätte es besser wissen müssen: Er kannte Jüngers politische Arbeit gut. Zu Beginn der 30er Jahre war Paetel Hauptschriftleiter der Zeitschrift Die Kommenden, deren Mitherausgeber Jünger war. 3

Als Paetel den Jünger der Marmorklippen (1939) in seiner inneren Emigration vorstellte, hatten Emigranten verschiedener Richtungen Jünger seinen Beitrag zur Zerstörung der Weimarer Republik längst zuerkannt. Siegfried Marck 4 , Hermann Rauschning 5 , Golo Mann 6 und Karl Löwith 7 sahen in Jünger einen Wegbereiter der deutschen Katastrophe. Vermutlich wußten sie von Jüngers tagespolitischem Geschäft in den Jahren 1925 bis 1930. In ihren Analysen waren sie jedoch nicht darauf eingegangen.

Selbst Armin Mohler hatte Jünger zu Lebzeiten nicht überzeugen können, seine politische Publizistik neu zu edieren. Zwei Gesamtausgaben erschienen ohne sie. Unbekannt war sie freilich nicht: In den Bibliographien Jüngers ist sie nahezu vollständig erfaßt. Dennoch sind die zum großen Teil schwer zugänglichen Texte weitgehend unbekannt geblieben.

Künftige Biographen mögen nun entscheiden, ob Jünger sein Denken und Handeln ehrlich oder selbstgerecht verarbeitete. Kurz nach dem Krieg war Jünger vorgeworfen worden, er wolle wie viele bloß Seismograph und Barometer, nicht aber Aktivist gewesen sein. 8 Ein anderer Zugang ist jedoch wichtiger. Die Bedeutung von Jüngers politischer Publizistik liegt weniger in ihrer Teilhabe am Gesamtwerk Jüngers, sondern in ihrem exemplarischen Charakter. Jünger spricht hier als Exemplar seiner Generation – einer Generation, die entscheidende lebensprägende Impulse nicht im Studium, sondern in den Erfahrungen an der Front und in den Wirren der gescheiterten Revolution sowie der katastrophalen wirtschaftlichen Lage bis zur Währungsreform im Dezember 1923 empfing.

Es ist oft betont worden, wie offen in der Spätphase der Weimarer Republik vielen Zeitgenossen die Zukunft schien. Zunächst bietet es sich daher an, Jüngers politische Publizistik zu lesen unter Einklammerung des Wissens um die weitere Entwicklung der deutschen Verhältnisse. Natürlich ist dies nur hypothetisch möglich und hat seine Grenzen. Die Perspektive des Zeitgenossen ist uns verschlossen. Wenn dieses Verfahren hier empfohlen wird, dann aus folgendem Grund: In den Diskussionen des Feuilleton wird der Blick auf Autoren wie Jünger in der Regel auf zwei Perspektiven verengt: Stellung zum Nationalsozialismus und zum Antisemitismus. Selbstverständlich sind dies Fragen, die immer wieder neu gestellt werden müssen. Nur: Jüngers Denken und seine Stellung in den Ideenzirkeln der intellektuellen Rechten wird so im Dunkeln bleiben. Die Kritik, die nur diese Maßstäbe kennt, und die Apologeten vom Schlage Paetels bewirken gemeinsam, daß die Komplexität der Weimarer Rechten, wie sie in so unterschiedlichen Werken wie denjenigen Armin Mohlers und Stefan Breuers erkannt wurde, aus dem Blick gerät.

Überblick

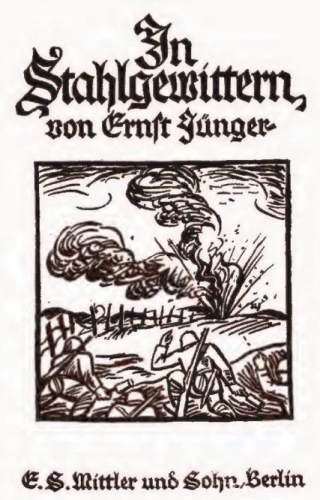

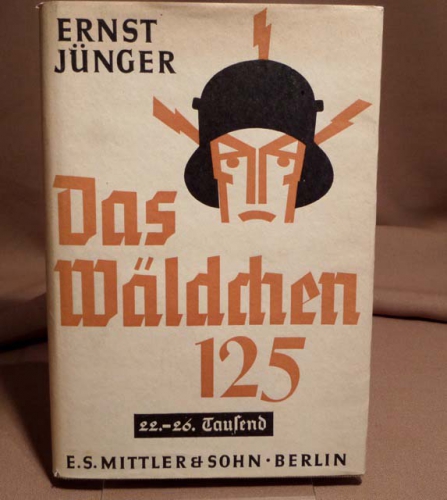

Der nun vorliegende Band Politische Publizistik 1919-1933 versammelt nicht nur die politische Publizistik jener Jahre, sondern auch eine Fülle anderer Texte, die diesem Genre nicht zugeordnet werden können. Insgesamt sind es 144 Texte. Die Vorworte zu verschiedenen Auflagen von In Stahlgewittern, von Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis , von Feuer und Blut und Das Wäldchen 125, die alle nicht in die Werkausgaben aufgenommen wurden, kommen ebenso zum Abdruck wie einige Rezensionen, die zwischen 1929 und 1933 entstanden.

Man könnte einwenden, daß der Band insgesamt ein heterogenes Sammelsurium von Texten der Jahre 1920–33 sei, und so gesehen der Titel der Ausgabe in die Irre führe. Auf der anderen Seite: Die Grenze zwischen politischen und unpolitischen Arbeiten ist bei einem Autor wie Jünger schwer zu ziehen. Und: die nun vorliegende Ausgabe hat einen eminenten Vorzug. Jüngers mitunter äußerst schwer zugängliche Arbeiten aus der Zeit der Weimarer Republik liegen nun – soweit sie bekannt sind – zum erstenmal vollständig vor. 9

Eingeleitet wird der Band von einigen kleineren Arbeiten, die ebenfalls nicht im strengen Sinn politisch zu nennen sind. Zwischen 1920 – dem Jahr, in dem In Stahlgewittern erschien – und 1923 schrieb Jünger einige kürzere Aufsätze, die Fragen der modernen Kriegsführung behandeln, im Militär-Wochenblatt. Zeitschrift für die deutsche Wehrmacht.

Am 31. August 1923 – in der Hochphase der Inflation – schied Jünger aus der Reichswehr aus. Im Wintersemester immatrikulierte er sich in Leipzig als stud. rer. nat. Jünger war damals 28 Jahre alt. In einer Lebensphase, in der wesentliche Prägungen bereits abgeschlossen sind, begann er zu studieren. Jünger hörte Zoologie bei dem Philosophen und Biologen Hans Driesch, dem führenden Sprecher des Neovitalismus, und Philosophie bei Felix Krüger und dessen Assistenten Hugo Fischer. Auch dürfte er Hans Freyer, der seit 1925 in Leipzig Professor war, an der Universität kennengelernt haben.

Seine erste politische Arbeit schrieb Jünger kurz nach seinem Ausscheiden aus der Reichswehr für den Völkischen Beobachter – einer von zwei Beiträgen in dieser Zeitung, der zweite erschien 1927. Im September 1923, knapp zwei Monate vor Hitlers Münchner Putschversuch, erscheint der Aufsatz mit dem Titel Revolution und Idee. Schon hier finden sich Motive, die sich durch Jüngers politisches Argumentieren der folgenden Jahre ziehen werden: die Bedeutung der Idee und die Unaufhaltsamkeit einer künftigen Revolution. Die gescheiterte Revolution von 1918, schrieb Jünger, "kein Schauspiel der Wiedergeburt, sondern das eines Schwarmes von Schmeißfliegen, der sich auf einen Leichnam stürzte, um von ihm zu zehren", war nicht in der Lage eine Idee zu verwirklichen. Sie mußte daher notwendig scheitern: "Für diese Tatsachen, die späteren Geschlechtern unglaublich vorkommen werden, gibt es nur eine Erklärung: der alte Staat hatte jenen rücksichtslosen Willen zum Leben verloren, der in solchen Zeiten unbedingt notwendig ist" (35). Es gilt daher einzusehen, daß die versäumte Revolution nachgeholt werden muß:

Die echte Revolution hat noch gar nicht stattgefunden, sie marschiert unaufhaltsam heran. Sie ist keine Reaktion, sondern eine wirkliche Revolution mit all ihren Kennzeichen und Äußerungen, ihre Idee ist die völkische, zu bisher nicht gekannter Schärfe geschliffen, ihr Banner ist das Hakenkreuz, ihre Ausdrucksform die Konzentration des Willens in einem einzigen Punkt – die Diktatur! Sie wird ersetzen das Wort durch die Tat, die Tinte durch das Blut, die Phrase durch das Opfer, die Feder durch das Schwert. (36)

1922 erscheint Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis und die zweite Auflage von In Stahlgewittern, 1923 im Hannoverschen Kurier in 16 Folgen die Erzählung Sturm, 1924 und 1925 Das Wäldchen 125. Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen und Feuer und Blut. Ein kleiner Ausschnitt aus einer großen Schlacht. Die erste Phase seines Werkes, in dem Jünger seine Fronterlebnisse verarbeitete, ist damit abgeschlossen. Das Jahr 1925 bedeutet für Jünger in vielerlei Hinsicht eine Zäsur. Zehn Jahre lang – bis zu den Afrikanischen Spielen von 1936 – wird Jünger keine Erzählungen und Romane veröffentlichen.

1922 erscheint Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis und die zweite Auflage von In Stahlgewittern, 1923 im Hannoverschen Kurier in 16 Folgen die Erzählung Sturm, 1924 und 1925 Das Wäldchen 125. Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen und Feuer und Blut. Ein kleiner Ausschnitt aus einer großen Schlacht. Die erste Phase seines Werkes, in dem Jünger seine Fronterlebnisse verarbeitete, ist damit abgeschlossen. Das Jahr 1925 bedeutet für Jünger in vielerlei Hinsicht eine Zäsur. Zehn Jahre lang – bis zu den Afrikanischen Spielen von 1936 – wird Jünger keine Erzählungen und Romane veröffentlichen.

In den zehn für das Schicksal Deutschlands entscheidenden Jahren von 1925–1935 schreibt Jünger Weltanschauungsprosa als politischer Publizist in einer Vielzahl meist rechtsstehender Organe, als Herausgeber verschiedener Sammelbände und als Essayist in den Büchern Das Abenteuerliche Herz (1929) und Der Arbeiter (1932). Aber das Jahr 1925 ist noch in anderer Hinsicht eine Zäsur: Jünger bricht das Studium ab und tritt in den bürgerlichen Stand der Ehe.

Dem im September 1923 im Völkischen Beobachter veröffentlichten Artikel folgt fast zwei Jahre lang keine im strengen Sinne politische Stellungnahme. Die regelmäßige politische Publizistik Jüngers beginnt am 31. August 1925 mit einem Aufsatz in der Zeitschrift Gewissen, dem Organ der sich um Arthur Moeller van den Bruck scharenden jungkonservativen >Ring-Bewegung<. Moderater im Ton als im Völkischen Beobachter finden sich die gleichen Forderungen wie zwei Jahre zuvor: Einsicht in die Bedeutung einer Idee und Notwendigkeit einer Revolution. Bemerkenswert ist der Publikationsort. Zwar lassen sich zwischen Jünger und dem Kreis um Moeller auch Gemeinsamkeiten nachweisen, aber in wesentlichen Punkten bestehen Differenzen – von ihnen wird später noch die Rede sein.

Jünger veröffentlichte seine politischen Traktate in einer Vielzahl auch Kennern der Zeitschriftenlandschaft der Weimarer Republik eher unbekannten Organen. 10 Man kann hier unterscheiden zwischen Zeitschriften, in denen Jünger als Gast schrieb – in der Regel gab es dann nur ein oder zwei Beiträge –, und solchen, in denen er regelmäßig zur Feder griff. Bei den meisten Zeitschriften, in denen Jünger regelmäßig schrieb, trat er auch als Mitherausgeber auf.

Jünger als Aktivist des Neuen Nationalismus in der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte (1925 / 26)

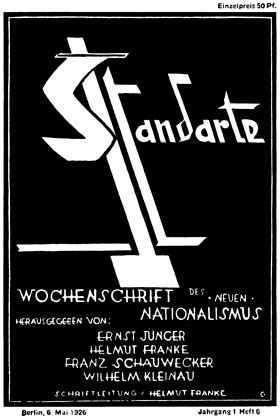

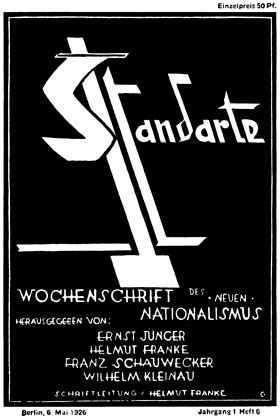

Die erste Zeitschrift, für die Jünger regelmäßig arbeitete, war das von ihm mitherausgegebene Blatt Die Standarte. Beiträge zur geistigen Vertiefung des Frontgedankens . Es erschien zum erstenmal im September als Sonderbeilage des Stahlhelm. Wochenschrift des Bundes der Frontsoldaten.

Mit dem Erscheinen dieser Beilage begann eine zunehmende Politisierung des Stahlhelm. Der im Dezember 1918 gegründete republikfeindlich eingestellte Bund der Frontsoldaten war schon aufgrund seiner hohen Mitgliederzahlen eine geeignete Zielgruppe für politische Agitation. 11 Bis zum Dezember schrieb Jünger für jede Nummer der wöchentlich erscheinenden Beilage. Diese insgesamt 17 Beiträge stehen in engem Zusammenhang, der letzte Beitrag erscheint als Schluß.

Von allen politischen Zeitschriftenarbeiten Jüngers dürften diejenigen in der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte die größte Wirkung gehabt haben. Die Wochenschrift des Stahlhelm hatte eine Auflage von 170 000 – eine Zahl, an die sämtliche anderen Zeitschriften, in denen Jünger veröffentlichte, nicht annähernd herankamen. Weil Jünger mit diesen Beiträgen vermutlich die größte Wirkung entfaltete, aber auch, weil sie für eine bestimmte Etappe in seinem politischem Schaffen stehen, sollen sie etwas ausführlicher behandelt werden.

Das Programm, das Jünger in der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte entwickelt, ist getragen von leidenschaftlicher Parteinahme für eine nationalistische Revolution. Auf einen Punkt von Jüngers Physiognomie der Gegenwart sind alle weiteren Überlegungen bezogen. Jünger lebt im Glauben, daß der große Krieg noch gar kein Ende gefunden habe, noch nicht endgültig verloren sei. Politik ist ihm daher eine Form des Krieges mit anderen Mitteln (S. 63f.). Die Generation der vom Krieg geprägten Frontsoldaten soll diesen Krieg fortsetzen. Jünger will nicht zurückschauen, sondern die Zukunft gestalten. Die Gruppe der Frontsoldaten, der sich Jünger zurechnet, muß daher versuchen, die Jugend zu gewinnen (S. 77).

Jüngers Programm nennt sich>Nationalismus<: "Ja wir sind nationalistisch, wir können gar nicht nationalistisch genug sein, und wir werden uns rastlos bemühen, die schärfsten Methoden zu finden, um diesem Nationalismus Gewalt und Nachdruck zu verleihen" (S. 163). Das nationalistische Programm soll auf vier Grundpfeilern basieren: Der kommende Staat muß national, sozial, wehrhaft und autoritativ gegliedert sein (S. 173, S. 179, S. 197, S. 218). Die "Staatsform ist uns nebensächlich, wenn nur ihre Verfassung eine scharf nationale ist" (S. 151). "Der Tag, an dem der parlamentarische Staat unter unserem Zugriff zusammenstürzt, und an dem wir die nationale Diktatur ausrufen, wird unser höchster Festtag sein" (S. 152). Mit dem Schlagwort Nationalismus ist wenig gesagt. Was ist es, das den Nationalismus des Frontsoldaten auszeichnet?

Durch den Krieg, so Jünger, wurde der von der wilhelminischen Epoche geprägte Frontsoldat in ganz andere Bahnen gerissen: "Er betrat eine neue, unbekannte Welt, und dieses Erlebnis rief in vielen jene völlige Veränderung des Wesens hervor, die sich am besten mit der religiösen Erscheinung der >Gnade< vergleichen läßt, durch welche der Mensch plötzlich und von Grund auf verwandelt wird" (S. 79).

Mit dem Ende des Kaiserreichs verbindet Jünger die Überwindung einer materialistischen Naturanschauung, der individualistischen Idee allgemeiner Menschenrechte und des bloßen Strebens nach materiellem Wohlstand. Dagegen behauptet er die Bedeutung der >Nachtseite< des Lebens. 12 Gegen das rationalistische, mechanistische, materialistische Denken des Verstandes setzt er das Gefühl und den organischen Zusammenhang mit dem Ganzen: "Für uns ist das Wichtigste nicht eine Revolution der staatlichen Form, sondern eine seelische Revolution, die aus dem Chaos neue, erdwüchsige Formen schafft." (S. 114).

Mit dem Ende des Kaiserreichs verbindet Jünger die Überwindung einer materialistischen Naturanschauung, der individualistischen Idee allgemeiner Menschenrechte und des bloßen Strebens nach materiellem Wohlstand. Dagegen behauptet er die Bedeutung der >Nachtseite< des Lebens. 12 Gegen das rationalistische, mechanistische, materialistische Denken des Verstandes setzt er das Gefühl und den organischen Zusammenhang mit dem Ganzen: "Für uns ist das Wichtigste nicht eine Revolution der staatlichen Form, sondern eine seelische Revolution, die aus dem Chaos neue, erdwüchsige Formen schafft." (S. 114).

Die Weltanschauung, die Jünger seiner Generation der Frontsoldaten empfiehlt, hat ihre Wurzeln in der Romantik und der Lebensphilosophie Nietzsches. Jünger betont die Bedeutung des Gefühls der Gemeinschaft, der Verbindung mit dem Ganzen, denn das Gefühl stehe am Anfang jeder großen Tat. Wachstum ist für Jünger das natürliche Recht alles Lebendigen (S. 82), das keines Beweises zu seiner Rechtfertigung bedarf (S. 186):

Alles Leben unterscheidet sich und ist schon deshalb kriegerisch gegeneinander gestellt. Im Verhältnis des Menschen zu Pflanzen und Tieren tritt das ohne weiteres hervor, jeder Mittagstisch liefert den unwiderleglichen Beweis. Das Leben äußert sich jedoch nicht nur im Kampfe der Arten untereinander, sondern auch im Kampfe innerhalb der Arten selbst. (S. 133) 13

Jünger hat den soziologischen Blick, der dem Konservatismus seit der Romantik eigen ist. Deutlich zeigt sich seine Aufnahme romantischen Geschichtsdenkens in der Betonung des Besonderen gegen das Allgemeine, seiner Betonung der Abhängigkeit "von unserer Zeit und unserem Raum" (S. 158). Er fordert, mit "dem unheilvollen Streben nach Objektivität, die nur zur relativistischen Aufhebung der Kräfte führt, aufzuräumen" und sich zu bewußter Einseitigkeit zu bekennen, "die auf Wertung und nicht auf >Verständnis< beruht" (S. 79f.).

Ein wichtiges Moment in Jüngers Geschichtsdenken ist das Verhältnis von soziologischer Diagnose und zukünftiger Aufgabe. Wenn Jünger bestimmte historische Entwicklungen untersucht, bemüht er häufig die Kategorie der Notwendigkeit. Ereignisse treten mit Notwendigkeit ein. In der gescheiterten Revolution "lag auch eine Notwendigkeit" (S. 110). Über die Entwicklung der Technik urteilt er: "Zwangsläufige Bewegungen lassen sich nicht aufhalten" (S. 160).

Hinter der Überzeugung, daß bestimmte Ereignisse mit Notwendigkeit eintreten, steht die Vorstellung einer überpersönlichen Idee, die sich in der Geschichte zu verwirklichen sucht: Im Krieg gibt es Augenblicke, in denen "die kriegerische Idee sich rein, vornehm und mit einer prächtigen Romantik offenbart. Dort werden Heldentaten verrichtet, in denen kaum noch der Mensch, sondern die kristall-klare Idee selbst am Werke scheint" (S. 109).

Über den geschichtsphilosophischen Schwung der Jahre, in denen diese Aufsätze entstanden sind, schrieb Jünger am 20. April 1943 rückblickend in seinem zweiten Pariser Tagebuch:

Es ist die Geschichte dieser Jahre mit ihren Denkern, ihren Tätern, Märtyrern und Statisten noch nicht geschrieben; wir lebten damals im Eie des Leviathans. [...] Die Mitspieler sind ermordet, emigriert, enttäuscht oder bekleiden hohe Posten in der Armee, der Abwehr, der Partei. Doch immer werden diejenigen, die noch auf Erden weilen, gern von jenen Zeiten sprechen; man lebte damals stark von der Idee. So stelle ich mir Robespierre in den Arras vor. 14

Für den Jünger der zwanziger Jahre gilt: Der Mensch ist nichts ohne eine Idee. Scheitert die Verwirklichung einer Idee, wie in der Novemberrevolution, so scheitert sie notwendig, weil sie noch nicht stark genug war. Die Zeit war dann noch nicht reif genug. Aufgabe des einzelnen ist es, sich in den Dienst der Idee zu stellen: Die großen geschichtlichen Leistungen besitzen die Eigenschaft, daß der "Mensch nur als Werkzeug einer höheren Vernunft" (S. 93) tätig ist. 15

Auch hier zeigt sich: Jüngers Geschichtsdenken kommt aus dem 19. Jahrhundert und zeigt den für die Ideenlehre der historischen Schule typischen Hang zur geschichtsphilosophischen Spekulation. Karl Löwith, der Jünger in der Folge Nietzsches sah, hat darauf hingewiesen, daß "Jünger selbst noch der bürgerlichen Epoche entstammt" und daher in der problematischen Lage sei, daß das Alte nicht mehr und das Neue noch nicht gilt. 16 Dies gilt weniger für die Inhalte, umsomehr aber für die Formen von Jüngers Denken.

Durch den Einfluß von Nietzsches vitalistischer Teleologie werden Jüngers geschichtsphilosophische Spekulationen auch biologisch fundiert: "Aber je mehr man beobachtet, desto mehr kommt man dazu, an die große geheimnisvolle Steuerung durch eine große biologische Vernunft zu glauben" (S. 171). 17 Und auch sein Begriff der Zeit zeigt Jünger, dem die Arbeiten Bergsons vertraut waren, in der Tradition des organologisch-lebensphilosophischen Denkens des 19. Jahrhunderts: Zeit ist ihm nichts Zufälliges, "sondern ein geheimnisvoller und bedeutungsvoller Strom, der jedes durchfließt und sein Inneres richtet, wie ein elektrischer Strom die Atome eines metallischen Körpers richtet und regiert" (S. 182).

>Konservative Revolution<

Die Hinweise auf die Wurzeln von Jüngers Denken erfolgen nicht in der Absicht, Jüngers Originalität zu schmälern oder der bekannten Linie das Wort zu reden, nach der die Lebensphilosophie in den Faschismus mündet. Vielmehr geht es darum, Jüngers Geschichtsdenken in Beziehung zu setzen zur sogenannten >Konservativen Revolution<. Es soll untersucht werden, ob Jüngers Denken als konservative Revolution im Sinne der als >Konservative Revolution< etikettierten Geistesrichtung der Weimarer Republik begriffen werden kann.

Jüngers revolutionäre Einstellung ist offenkundig. Weniger deutlich ist, inwiefern sein Denken >konservativ<genannt werden kann. Das wichtigste >konservative< Moment in Jüngers Denken liegt in der Bedeutung der Gemeinschaft.

Das Gefühl der >Gemeinschaft in einem großen Schicksal<, das am Beginn des Krieges stand, das Bewußtsein der Idee der Nation und die gemeinsame >Unterwerfung unter eine Idee< sind für Jünger Zeichen einer grundsätzlichen Kurskorrektur: "Wir erblicken darin die erste Anknüpfung einer verloren gegangenen Verbindung, die Offenbarung einer höheren Sicherheit, die sich im Persönlichen als Instinkt äußert" (S. 86).

Jünger bejaht die Revolution, aber er schränkt ihre Bedeutung zugleich ein, indem er sie als Methode und nicht als Ziel begreift. Sie kann nur Methode sein, denn der "Frontsoldat besitzt Tradition und weiß, daß alle Größe und Macht organisch gewachsen sein muß, und nicht aus der reinen Verneinung, aus dem leeren Dunst herausgegriffen werden kann. Wie er den Krieg nicht verleugnet, sondern aus ihm als einer stolzen Erinnerung heraus die Kraft zu neuen Aufgaben zu schöpfen sucht, so fühlt er sich auch nicht berufen, das zu verachten, was die Väter geleistet haben, sondern er sieht darin die beste und sicherste Grundlage für das neue größere Reich." (S. 124f.; vgl. S. 128f.)

Die Denkfigur einer >Konservativen Revolution< zielt auf den Versuch, einen organischen Zusammenhang wiederherzustellen. Das Eintreten für eine >Konservative Revolution< lebt also wesentlich von der Entscheidung, an welche gewachsenen Traditionen wieder angeschlossen werden soll. Jüngers Forderung nach einer Revolution, die an die Tradition anschließt, bestimmt sich aber im wesentlichen ex negativo. Die Verbindung, die Jünger zwischen seiner historistischen Lebensphilosophie und seinem Nationalismus herstellen will, bleibt so rein äußerlicher Natur. Es fehlt ihr der Nachweis eines inneren Zusammenhanges.

Ein Argument für diesen Zusammenhang bleibt nur der Versuch, das Individuum auf der Ebene des Gefühls an die organisch gewachsene Nation zu binden. Die Bildung der Nation müßte aber nicht zwingend auf Jüngers Fassung eines autoritativen Nationalismus hinauslaufen. Lediglich die Opposition zu bestimmten Weltanschauungen ist durch den Willen, das Individuum organisch einzubinden, notwendig. Für die Krise des entwurzelten Individuums ist diesem Willen gemäß der Liberalismus und mit ihm die Idee der parlamentarischen Demokratie verantwortlich.

Die großen Gefahren sieht Jünger daher "nicht im marxistischen Bollwerk" (S. 148, S. 151), sondern in allem, was mit dem Liberalismus zusammenhängt: Die "Frage des Eigentums gehört nicht zu den wesentlichen, die uns vom Kommunismus trennen. Sicher steht uns der Kommunismus als Kampfbewegung näher als die Demokratie, und sicher wird irgendein Ausgleich, sei er friedlicher oder bewaffneter Natur erfolgen müssen"(S. 117).

Nach der Trennung vom Stahlhelm

Schon die 19 Aufsätze in der Beilage Die Standarte zwischen September 1925 und März 1926 würden ausreichen, um das Urteil zu korrigieren, Jünger sei im Grunde ein unpolitischer Einzelgänger gewesen. Unabhängig von den politischen Bekenntnissen, die Jünger abgibt, wird dies schon durch seine leidenschaftliche Parteinahme deutlich. Aber auch später spricht Jünger von dem kleinen Kreis, dem er angehöre (S. 197), und greift immer wieder auf die Wir-Form zurück: "Wir Nationalisten" (S. 207). Ein Aufsatz beginnt mit der Anrede: "Nationalisten! Frontsoldaten und Arbeiter!" (S. 250) Und in einem anderen heißt es: "ich spreche im Namen von hunderttausend Frontsoldaten" (S. 267).

Um so erstaunlicher ist es, daß der Herausgeber Sven Berggötz in seinem Nachwort schreibt, Jünger hätte zwar durchaus einen beachtlichen Leserkreis erreicht, aber dieser hätte "sich weitgehend auf Leser mit einem ähnlichen Erfahrungshintergrund beschränkt". So habe er zwar auf die Meinungsbildung eingewirkt, aber "mit Sicherheit nicht in signifikanter Weise Einfluß auf die öffentliche Meinung genommen" (S. 867).

Weshalb 170 000 den Stahlhelm lesende ehemalige Frontsoldaten nicht zur öffentlichen Meinung zählen, bleibt Berggötz' Geheimnis – oder wollte Berggötz bloß sagen, die Stahlhelmer dachten ohnehin schon, was Jünger formulierte? Von welchem Autor ließe sich dann nicht behaupten, er artikuliere nur, was andere denken? Noch unverständlicher ist aber sein abschließendes Urteil: "Letztlich war Jünger schon damals ein im Grunde unpolitischer Mensch, der im wesentlichen utopische Vorstellungen vertrat." (S. 868) Als ob Utopie und Politik einen Gegensatz darstellten. 18

Der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte war keine lange Lebenszeit beschieden. Schon nach sieben Monaten erschien Die Standarte im März 1926 nach Unstimmigkeiten mit der Bundesleitung des Stahlhelm zum letzten Mal. Nachfolgeorgan war die fast gleichnamige Standarte. Wochenschrift des neuen Nationalismus, die nun selbständig erschien – herausgegeben von Ernst Jünger, Helmuth Franke, Franz Schauwecker und Wilhelm Kleinau. Ihre Auflage von vermutlich wenigen Tausend Exemplaren reichte nicht annähernd an Die Standarte heran.

Das Selbstverständnis der Herausgeber wird in einem programmatischen Beitrag Helmut Frankes für die erste Nummer der neuen Standarte deutlich: "Wir Standarten-Leute kommen aus allen Lagern: Vom konservativen bis zum jungsozialistischen. Die faschistische Schicht hat kein Programm. Sie wächst und handelt. " 19

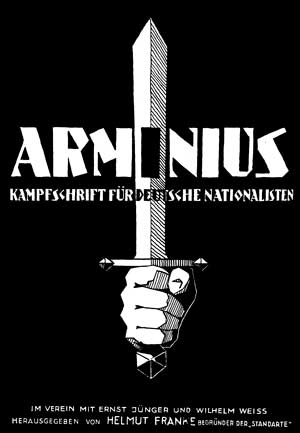

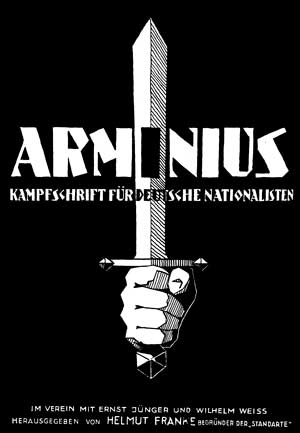

Auch die Standarte erschien nicht lange. Im August 1926 wurde die Zeitschrift vorübergehend verboten, weil in dem Artikel Nationalistische Märtyrer die Morde an Walther Rathenau und Matthias Erzberger legitimiert worden waren. Im November 1926 gründete Jünger mit Helmut Franke und Wilhelm Weiss die nächste Zeitschrift: Arminius. Kampfschrift für deutsche Nationalisten (teilweise mit dem Nebentitel: Neue Standarte), die bis September 1927 existierte. Im Oktober 1927 gründete Jünger mit Werner Lass die Zeitschrift Vormarsch. Blätter der nationalistischen Jugend, die bis 1929 erschien. Die nächste Zeitschrift war ebenfalls ein Gemeinschaftsprojekt von Jünger und Werner Lass. Von Januar 1930 bis Juli 1931 gaben sie die Zeitschrift Die Kommenden. Überbündische Wochenschrift der deutschen Jugend heraus.

Zwischen 1926 und 1930 war Jünger also nahezu ununterbrochen in die Herausgabe von Zeitschriften involviert. Neben einer Vielzahl von Beiträgen, die er für seine Zeitschriften schrieb, veröffentlichte Jünger auch in einigen anderen Organen, z. B. in Wilhelm Stapels Deutschem Volkstum.

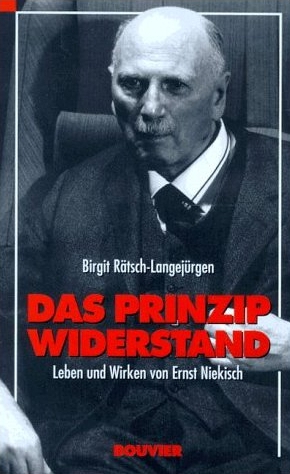

Einzelne Beiträge erschienen auch in Zeitschriften der demokratischen Linken, in Willy Haas' Literarischer Welt und in Leopold Schwarzschilds Das Tagebuch. Hier stellte Jünger seinen Nationalismus vor. Eine größere Zahl von Beiträgen plazierte Jünger in Ernst Niekischs Widerstand. Zeitschrift für nationalrevolutionäre Politik. Nach 1931 schrieb er fast nur noch in diesem Blatt. Die Hauptphase seiner politischen Arbeiten endet 1930.

Jünger und die Jungkonservativen

Nachdem die Stahlhelmleitung im Oktober 1926 die Parole >Hinein in den Staat< ausgegeben hatte, ging Jünger scharf auf Distanz. Im November 1926 äußerte er seine Befremdung ob der Ereignisse im Stahlhelm und reagierte: Der Wille müsse frei gemacht werden von "organisatorischen Verbindungen, die sich als Fessel" erwiesen haben (S. 258): "Reine Bewegung, aber nicht Bindung fordern wir" (S. 259, vgl. S. 256). Im Februar 1927 wiederholte er im Arminius seinen Angriff: Der Stahlhelm ist "bürgerlicher und damit liberalistischer Natur" (S. 305).

Hinter dem Bekenntnis zum Staat, das die Stahlhelmleitung verkündet hatte, vermutete Jünger bestimmte Interessengruppen: Man "bemühe sich mit Hilfe zur Verstärkung herbeigerufener Routiniers, die sich durch jahrelange Tätigkeit an jenen esoterischen Debattierklubs in Berlin W. ein Höchstmaß an politischer Balancierkunst erworben haben, die Hineinparole so zu verklausulieren, daß sie ebensogut sie selbst wie ihr Gegenteil sein kann" (S. 305).

Nachdem Jünger und seine Mitstreiter aus dem Stahlhelm zurückgedrängt worden waren, gewannen Mitglieder des Juniklubs zunehmend Einfluß. 20 Neben Heinz Brauweiler, dem Theoretiker des Ständestaats, tat sich vor allem der >Antibolschewist< Eduard Stadtler hervor. 21 Stadtler war vor dem Krieg Sekretär der Jugendbewegung der Zentrumspartei. Nach dem Krieg wurde er durch die Gründung der Antibolschewistischen Liga bekannt. Stadtler gehörte zu den ersten, die eine Verbindung von Konservatismus und Revolution als Programm expressis verbis formulierten. 22 Anfang der zwanziger Jahre war er eine der führenden Figuren des Juniklubs.

Versteht man unter >Konservativer Revolution< eine politische Richtung, den Zusammenhang verschiedener Personen und Gruppen, die ein gemeinsames politisches Ziel haben, so ist zu klären, in welchem Verhältnis diese Personen zueinander standen, wo und wie sie sich organisierten.

Im August 1926 hatte Jünger geschrieben: "Dieser Nationalismus ist ein großstädtisches Gefühl" (S. 234). Im Juni 1927 zog er mit seiner jungen Familie von Leipzig nach Berlin um. Zunächst wohnte er in der Nollendorfstraße in Schöneberg, also in unmittelbarer Nähe der Motzstraße, wo die Jungkonservativen im Schutzbundhaus in der Nr. 22 ihre Zusammenkünfte abhielten. Jünger blieb nicht lange in West-Berlin. Bereits nach einem Jahr siedelte er um in den Ostteil der Stadt, in die Stralauer Allee, wo vornehmlich Arbeiter wohnten. 23 1931 zog Jünger in die Dortmunder Straße, nähe Bellevue, 1932 in das ruhige, bürgerliche Steglitz.

Natürlich kann man aus dem Wechsel der Wohnorte nicht einfach auf die Entwicklung eines Denkens schließen. Aber es wird kein bloßer Zufall gewesen sein, daß Jünger zunächst in so unmittelbarer Nähe der Motzstraße wohnte, daß er den Arbeiter schrieb und in einem Arbeiterviertel wohnte, daß sein allmählicher Rückzug aus der politischen Agitation mit dem Umzug nach Steglitz zusammenfiel.

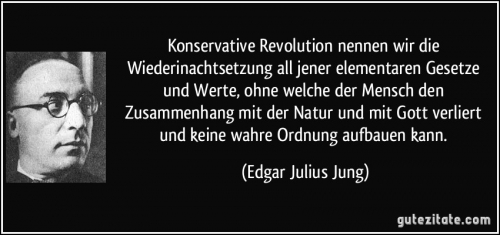

Über die Kontakte Jüngers zu den Jungkonservativen ist wenig bekannt. Hans-Joachim Schwierskott hat seiner Biographie Moellers eine Mitgliederliste der Jungkonservativen beigegeben, in der sich auch der Name Jüngers findet. 24 Aber das Verhältnis zwischen Jünger und den Jungkonservativen war gespannt. In seinen politischen Arbeiten erwähnt Jünger Moeller gelegentlich, aber neben einer Anspielung auf Edgar Julius Jungs Buch Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen (S. 432) gibt es kaum explizite Hinweise auf eine Auseinandersetzung mit den Jungkonservativen.

Der erwähnte Angriff auf die "esoterischen Debattierclubs in Berlin-West" deutet darauf hin, daß Jünger in für ihn wesentlichen Punkten Differenzen zwischen sich und Jungkonservativen wie Eduard Stadtler, Max Hildebert Boehm oder Edgar Julius Jung sah. Vermutlich waren sie ihm zu bürgerlich, zu liberal, zu christlich, zu sehr im Staat. Den Gedanken einer hierarchisch geprägten Stände-Gesellschaft lehnte Jünger vehement ab: "Aufgrund des Blutes und des Charakters wollen wir uns in Gemeinschaften und immer größere Gemeinschaften binden, ohne Rücksicht auf Wissen, Stand und Besitz, und uns klar trennen und scheiden von allem, was nicht in diese Gemeinschaften gehört" (S. 212).

Aus den Reihen der sich um den 1925 verstorbenen Moeller van den Bruck gruppierenden Jungkonservativen sollte Jünger später heftig attackiert werden. Seine konsequenten Angriffe auf alles Bürgerliche – ein Grundmotiv der politischen Publizistik, das er im Arbeiter besonders radikal vertrat – brachte Jünger eine heftige Replik seitens Max Hildebert Boehms ein. 25 Aber Jünger hat von Seiten der Jungkonservativen auch Zuspruch gefunden. Der Philosoph Albert Dietrich, ein Schüler Ernst Troeltschs und Mitglied des Juniklubs seit der ersten Stunde, überwarf sich mit Boehm über dessen Angriff auf Jünger. 26 Auch hatte Jünger gute Kontakte zu einem anderen Flügel der Jungkonservativen Bewegung‚ zum sogenannten >Tatkreis< um Hans Zehrer, Giselher Wirsing und Ferdinand Fried. 27

Deutungsmöglichkeiten

Ob die Zuordnung Jüngers zur >Konservativen Revolution< gerechtfertigt ist, kann nicht pauschal entschieden werden. Zumindest drei Unterscheidungen bieten sich an.

Es sind erstens die personellen Verbindungen zu betrachten. Sie können Zeichen sein für ein gemeinsames Arbeiten an gemeinsamen Zielen, auch wenn in letzter Instanz die Ziele nicht die gleichen sind. Zweitens sind die konkreten politischen Positionen zu untersuchen und zu vergleichen. Und drittens ist nach Gemeinsamkeiten der Denkstile, der Denkfiguren, der Mentalität zu suchen.

Es sind erstens die personellen Verbindungen zu betrachten. Sie können Zeichen sein für ein gemeinsames Arbeiten an gemeinsamen Zielen, auch wenn in letzter Instanz die Ziele nicht die gleichen sind. Zweitens sind die konkreten politischen Positionen zu untersuchen und zu vergleichen. Und drittens ist nach Gemeinsamkeiten der Denkstile, der Denkfiguren, der Mentalität zu suchen.

Über die erste Möglichkeit einer Zuordnung sind bereits einige Anmerkungen gemacht worden. Ihre Bearbeitung erfordert die umfangreiche Sichtung der Nachlässe, um anhand von Briefzeugnissen und anderen persönlichen Dokumenten bekannte und unbekannte Verbindungen zu rekonstruieren.

Die zweite Möglichkeit ist durch die Arbeiten Stefan Breuers sehr erhellt worden. Breuer hat in einem Vergleich der konkreten politischen Positionen einer großen Gruppe von Autoren und Strömungen, die Armin Mohler und einige andere als >Konservative Revolution< bezeichnet haben, eindrucksvoll gezeigt, daß sich insgesamt betrachtet eine im einzelnen auch noch unterschiedlich weit gehende Liberalismuskritik als einziger gemeinsamer Nenner ausmachen läßt.

Dies ist nach Breuer zu wenig, um von einem einheitlichen Gebilde zu sprechen, da eine vehemente Kritik des Liberalismus auch von anderer Seite geübt wurde. Die Rede von der >Konservativen Revolution<, so Breuer, sei daher aufzugeben, da es sich um einen im wesentlichen auf Mohler zurückgehenden Mythos der Forschung handle. 28

Die Suche nach einheitsstiftenden Momenten der >Konservativen Revolution< kann auch jenseits konkreter politischer Programme auf der Ebene der Denkstile und der Mentalität ansetzen. Für Mohler ist diese dritte Möglichkeit die entscheidende. Nach Mohler ist das entscheidende Leitbild die "ewige Wiederkehr des Gleichen" Er versteht dieses Bild als den Versuch, die christliche Auffassung der Geschichte zu sprengen. Das Bild "der ewigen Wiederkehr des Gleichen" biete ein Gegenstück zum linearen Modell der Zeit, an welches die Idee des Fortschritts gekoppelt sei.

Zwar meint Mohler, daß es nicht für alle, die er der >Konservativen Revolution< zurechnet, "in gleichem Maße verpflichtend" sei, aber ihre wesentliche Denkfigur sieht er in den Gedanken Nietzsches vorgebildet. Er folgt Nietzsche in dem Dreischritt: Diagnose des Wertezerfalls, Affirmation dieses Prozesses (Nihilismus) bis zur Vollendung der Zerstörung der alten (christlichen) Werte, damit die Zerstörung in Schöpfung umschlagen kann. 29

Auch Breuer findet auf der Ebene der Mentalität eine Gemeinsamkeit der >Konservativen Revolution<. Während er in den konkreten politischen Positionen keine hinreichende Übereinstimmung findet, die es nahelegen würde, von der >Konservativen Revolution< zu sprechen, sieht er bei allen Autoren eine "Kombination von Apokalyptik, Gewaltbereitschaft und Männerbündlertum" 30 . Diese Bestimmung ist jedoch, wie Breuer selbst bemerkt, zu weit und unbestimmt, und daher ebenso unbefriedigend wie die Bestimmung über die gemeinsame Kritik am Liberalismus.

Mohlers Bestimmung hingegen ist zu eng. Die Unterstellung, der >Konservativen Revolution< sei eine antichristliche Stoßrichtung genuin inhärent, ist denn auch unmittelbar nach Erscheinen der ersten Auflage seines Buches stark kritisiert worden. 31

In der Linie dieser Kritik kann man gegen Mohler einwenden, einseitig einen eher unorganischen Begriff des Konservatismus in den Mittelpunkt gestellt zu haben. Wenn Mohler, die Formulierung Albrecht Erich Günthers aufgreifend, das Konservative versteht "nicht als ein Hängen an dem, was gestern war, sondern an dem was immer gilt", so betont er nur ein Moment des Konservatismus. 32 Denn der deutsche Konservatismus ist seit seinen Ursprüngen in der Romantik weitgehend organologisch und historistisch, d. h. mehr dem Gedanken organischer Entwicklung und einer sich entwickelnden und unterschiedlich ausgestaltenden Wahrheit als dem überzeitlicher Geltung verpflichtet.

In Mohlers Bestimmung des Konservativen ist die Tradition des romantischen Konservatismus – also gerade die Tradition, der die meisten Jungkonservativen verpflichtet sind – zu sehr in den Hintergrund gerückt. 33 So ergibt sich ein schiefes Bild: Diejenige Gruppe, die die Parole >Konservative Revolution< populär gemacht hat, ist in Mohlers Fassung der >Konservativen Revolution< eine Randgruppe, der eine "nur sehr bedingte revolutionäre Haltung" attestiert wird. 34

Nur folgerichtig ist daher Mohlers Vermutung, daß bei der Verbindung von jungkonservativem Christentum und seinem Leitbild der >Konservativen Revolution< eines von beidem Schaden leide.

Zu den Merkmalen organologischen Denkens im deutschen Konservatismus sind im wesentlichen zwei Momente zu zählen: Zum einen die Annahme einer Eingebundenheit des Einzelnen in die Gemeinschaft, zum anderen ein Bild der Geschichte, nach dem eines aus dem anderen wachsen soll. Konservativ sein, bedeutet seit Edmund Burkes Kritik der Französischen Revolution eine kritische Haltung gegenüber jeder radikalen gesellschaftlichen Veränderung. Nicht Veränderung überhaupt, sondern jede Veränderung, die sich nicht in einer Gemeinschaft organisch entwickelt, wird vom konservativen Standpunkt abgelehnt.

Indem der Konservatismus seine Wurzeln in der Kritik der französischen Revolution hat, ist ihm von Beginn an die aporetische Struktur einer >Konservativen Revolution< eigen. 35 Ist der organische Zusammenhang einmal aufgebrochen, muß sich der Konservative eines Mittels bedienen, das er eigentlich ablehnt. Er muß durch einen radikalen Schritt wieder versuchen, gemeinschaftliche Bindung zu gewinnen. Kein Konservatismus kann seine Werte erst neu schaffen.

Aber je tiefer die in der Vergangenheit liegenden Werte verschüttet sind, desto schwieriger wird der Versuch, wieder einen Anschluß zu gewinnen. Nach dem ersten Weltkrieg ist der Konservatismus in Deutschland in einer Verfassung, in der über den Gehalt der Werte der Gemeinschaft – wie die Untersuchungen Breuers zeigen – keine Einigkeit mehr besteht.

Der Schluß, den Breuer aus diesem Ergebnis zieht, daß man besser nicht mehr von der >Konservativen Revolution< sprechen sollte, könnte dennoch verfrüht sein. Denn es könnte ja entweder sein, daß die Formel >Konservative Revolution< eine gemeinsame Denkfigur verschiedener Gruppen benennt, oder aber, daß zwar sinnvoll von der >Konservativen Revolution< gesprochen werden kann, die Gruppe derer, die ihr angehören, jedoch enger gezogen werden muß, als in den Arbeiten Mohlers und seiner Nachfolger.

Konservativ ?

In eigener Sache hat Jünger das Bild einer >Konservativen Revolution< nicht verwendet. Schon der Begriff >konservativ< für sich genommen bezeichnet für Jünger in der Regel etwas ihm Fremdes (218). In Sgrafitti blickte er 1960 mit Distanz auf die Idee einer >Konservativen Revolution< zurück. 36

Er selbst zählte sich ganz offensichtlich nicht zur >Konservativen Revolution<. Alfred Andersch gegenüber bekannte er im Juni 1977: "Sie rechnen mich nicht den Konservativ-Nationalen, sondern den Nationalisten zu. Rückblickend stimme ich dem zu. " 37

Daß sich bei Jünger die Formulierung >Konservative Revolution< nicht in eigener Sache findet, muß nicht bedeuten, daß sich nicht wesentliche ihrer Momente bei ihm aufweisen lassen. Jünger glaubte ja, nur auf dem Weg einer Revolution könne eine Überwindung der mißlichen Gegenwart gelingen.

Die Frage bleibt nur, inwiefern die erstrebten Veränderungen als konservativ aufgefaßt werden können. In den Aufsätzen der Jahre 1925 und 1926 fanden sich einige für das Denken des Konservativen typische Momente: die Bedeutung der Gemeinschaft und die Bedeutung der Tradition.

Etwa ab dem Frühjahr 1926 – in einer Phase, die politisch zu den stabilsten der Weimarer Republik gehörte – wird Jünger in seinen Positionen jedoch immer radikaler. Von einer Bedeutung der Tradition ist nicht mehr die Rede.

Bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung ist eine Veränderung seines Denkens nicht zu erkennen, denn noch im September 1929 bestimmt er den Charakter des Nationalismus wie ehedem durch Angabe der genannten vier Punkte: Der Nationalismus strebe den national, sozial, wehrhaft und autoritativ gegliederten Staat aller Deutschen an (S. 504). Immer wieder kehren die Motive, daß das Sterben der Soldaten im großen Krieg einen Sinn gehabt habe (S. 239), daß alles Wesentliche nur erfühlt und nicht begriffen werden könne (S. 288).

Bestimmend bleibt auch die Bedeutung der Idee: "Nach neuen Zielen verlangt unser Blut, es fordert Ideen, an denen es sich berauschen, Bewegungen, in denen es sich erschöpfen und Opfer, durch die es sich selbst verleugnen kann" (S. 196).

Bestimmend bleibt auch die Bedeutung der Idee: "Nach neuen Zielen verlangt unser Blut, es fordert Ideen, an denen es sich berauschen, Bewegungen, in denen es sich erschöpfen und Opfer, durch die es sich selbst verleugnen kann" (S. 196).

Etwa seit Mitte 1926 zeigen sich deutliche Akzentverschiebungen. Immer stärker hebt Jünger nun die Notwendigkeit reiner Bewegung, reiner Dynamik hervor: Die Stärke einer Aktion besteht darin, "daß sie zu hundert Prozent Bewegung bleibt" (S. 256, vgl. auch S. 267). 38 Jüngers eigene Einschätzung gibt eine interessante Beschreibung der kollektiven Psyche seiner Generation: "Wir sind Dreißigjährige, früh durch eine harte Schule gegangen, und was sich in uns nicht gefestigt hat, das wird nicht mehr zu festigen sein." (S. 206)

Der Bruch mit dem Stahlhelm war mehr als ein tagespolitisches Ereignis. Er markiert den Beginn eines neuen Angriffs. Jünger fordert weiter, aber forcierter als bisher, die Revolution und den Bruch mit der Demokratie. Mit dem Ehrentitel Nationalisten wollen sich er und die seinen – "Männer, die gefährlich sind, weil es ihnen eine Lust ist, gefährlich zu sein" – vom "friedlichen Bürger" abwenden, schreibt er im Mai 1926 (S. 213). Der Nationalist habe

die heilige Pflicht, Deutschland die erste wirkliche, das heißt von sich rücksichtslos bahnbrechenden Ideen getriebene Revolution zu schenken. Revolution, Revolution! Das ist es, was unaufhörlich gepredigt werden muß, gehässig, systematisch, unerbittlich, und sollte dieses Predigen zehn Jahre lang dauern. [...] Die nationalistische Revolution braucht keine Prediger von Ruhe und Ordnung, sie braucht Verkünder des Satzes: >Der Herr wird über Euch kommen mit der Härte des Schwerts!< Sie soll den Namen Revolution von jener Lächerlichkeit befreien, mit der er in Deutschland seit fast hundert Jahren behaftet ist. Im großen Kriege hat sich ein neuer gefährlicher Menschenschlag entwickelt, bringen wir diesen Schlag zur Aktion! (S. 215)

Seine grundsätzliche Ablehnung der Demokratie brachte Jünger in einem Punkt immer wieder in Distanz zum Nationalsozialismus. Vor den Wahlen schrieb er im August 1926: "es bedeutet einen verhängnisvollen Zwiespalt, eine Einrichtung als theoretisch unsittlich zu erklären und gleichzeitig praktisch an ihr teilzunehmen. [...] Was gefordert werden muß, ist ein allgemeines striktes Verbot, an einer Wahl teilzunehmen" (S. 243ff.).

Schon früher hatte Jünger deutlich gemacht, daß er keinen unüberwindbaren Gegensatz zwischen Sozialismus und Nationalismus entdecken könne. Im Dezember 1926 bekannte er sich offen zur bolschewistischen Wirtschaftspolitik: "Wir suchen die Wirtschaftsführer davon zu überzeugen, daß unser Weg auf geradester Linie zu jener staatlich geordneten Zentralisation führt, die uns allein konkurrenzfähig erhalten kann." (S. 269)

Historismus

Mit der Liberalismuskritik der Romantik, mit den >Ideen von 1914<, teilt Jünger weiter wesentliche Überzeugungen: Es gebe kein moralisches Gesetz an sich, jedes Gesetz werde durch den Charakter bestimmt. Denn Charaktere "sind nicht den Gesetzen des Fortschrittes, sondern denen der Entwicklung unterworfen. Wie in der Eichel schon der Eichbaum vorausbestimmt ist, so liegt im Charakter des Kindes schon der des Erwachsenen" (S. 210). Allgemeine Wahrheiten, eine allgemeine Moral läßt Jüngers Historismus nicht gelten:

Wir glauben vielmehr an ein schärfstes Bedingtsein von Wahrheit, Recht, Moral durch Zeit, Raum und Blut. Wir glauben an den Wert des Besonderen. [...] Aber ob man an das Allgemeine oder das Besondere glaubt, das ist nicht das Wesentliche, wie am Glauben überhaupt nicht die Inhalte das Wesentliche sind, sondern seine Glut und seine absolute Kraft. (S. 280)

Jünger nimmt hier – im Januar 1927 – ein zentrales Motiv des Abenteuerlichen Herzens vorweg: "Ein Recht ist nicht, sondern wird gesetzt, und zwar nicht vom Allgemeinen, sondern vom Besonderen" (S. 283). Im Abenteuerlichen Herz heißt es noch eindrücklicher: "Daher kommt es, daß diese Zeit eine Tugend vor allen anderen verlangt: die der Entschiedenheit. Es kommt darauf an, wollen und glauben zu können, ganz abgesehen von den Inhalten, die sich dieses Wollen und Glauben gibt." 39

Wenn die Einsicht in die historische Gewordenheit die Absolutheit jeder Weltanschauung in Frage stellt, kann dies dazu führen, daß keine wahrer und damit verbindlicher scheint als die andere. In so einer Zeit mag es durchaus sinnvoll sein, für die Bedeutung der Entscheidung, ja für die Notwendigkeit der Entscheidung einzutreten. Wenn aber das >wofür< der Entscheidung beliebig wird, man sich nicht für eine Position entscheidet, für die man zwar keine rationalen Gründe, aber immer noch Gründe anzuführen vermag, dann handelt es sich, wie Jünger ja auch selbst gesehen hat, um reinen Nihilismus. Ob man diesen Nihilismus als Stadium des Übergangs begreift oder nicht, mit einer konservativen Haltung ist diese Position nicht mehr in Einklang zu bringen.

Antihistorismus

Im September 1929 erschien in dem von Leopold Schwarzschild herausgegebenen linksliberalen Tagebuch ein Aufsatz Jüngers, in dem seine Stellung zum Konservatismus besonders deutlich wird. Jünger war von Schwarzschild aufgefordert worden, seine Position darzustellen. Unmittelbarer Anlaß waren die Attentate der Landvolkbewegung, die in der Presse heftig diskutiert wurden.

Jünger wurde vorgestellt als "unbestrittener geistiger Führer" des jungen Nationalismus, für den "sogar Hugenberg, Hitler und die Kommunisten reaktionäre Spießbürger" (S. 788) sind. Jünger stellte klar, daß sein Nationalismus mit dem "Konservativismus" nicht "das mindeste zu schaffen" habe (S. 504, vgl. S. 218). 40 Seine Kritik an der parlamentarischen Demokratie trifft jeden, der sich nicht außerhalb der Ordnung des bestehenden Systems stellt. Letztlich sind ihm alle revolutionären Kräfte innerhalb eines Staates unsichtbare Verbündete (S. 506). Zerstörung sei daher das einzig angemessene Mittel: "Weil wir die echten, wahren und unerbittlichen Feinde des Bürgers sind, macht uns seine Verwesung Spaß" (S. 507). 41

Der Aufsatz im Tagebuch löste eine rege Diskussion um Jüngers Standort aus. Wenige Monate später, im Januar 1930, nahm Jünger in Niekischs Widerstand dazu Stellung ( Schlußwort zu einem Aufsatze): Die "Wendung zur Anarchie" habe sich "endgültig im Jahr 1927" vollzogen, zunächst sei sie jedoch nur "im kleinsten Kreis" zur Sprache gekommen.

Vor mir liegen meine Briefbände aus diesem Jahr, die mit Ausführungen gespickt sind über das, was wir damals den Nihilismus nannten, und dem wir morgen vielleicht wieder einen anderen Namen geben werden - vielleicht sogar den des Konservativismus, wenn es uns Vergnügen macht. Denn Chaos und Ordnung besitzen eine engere Verwandtschaft als mancher Glauben mag. (S. 541) 42

In einem der Briefe, aus denen Jünger zwei längere Passagen zitiert, heißt es, "wir" seien "als Glieder einer Generation vorläufig nur echt", "als wir durch den Nihilismus hindurchgehen und unseren Glauben noch nicht formulieren" (S. 542f.). Jünger kommentiert: Diesen Gedankengängen liege das Bestreben zu Grunde, "das Sein von allen Gewordenen Gebilden zu lösen, um es tieferen und furchtbareren Gewalten anzuvertrauen – solchen, die nicht das Opfer, sondern die Triebkräfte der Katastrophe sind" (S. 543).

Was Jünger und seinem Kreis vorschwebte war also ein radikaler Bruch mit der geschichtlichen Überlieferung überhaupt. Aus der Sicht des deutschen Konservatismus kann man nicht antikonservativer eingestellt sein. Jünger war sich dieses Antikonservatismus vollends bewußt, indem er ihm einen anderen Konservatismus gegenüberstellte:

Die Ursprünglichkeit des Konservativen zeichnet sich dadurch aus, daß sie sehr alt, die des Revolutionärs, daß sie sehr jung sein muß. Die Konservativen von heute sind aber fast ohne Ausnahme erst hundert Jahre alt. [...] Mit anderen Worten: Der Bannkreis des Liberalismus hat größere Reichweite, als man im allgemeinen glaubt, und fast jede Auseinandersetzung vollzieht sich innerhalb seines Umkreises. (S. 589)

In den Aufsätzen des Jahres 1930 manifestierte sich der antihistoristische Affekt weiter. 43 Im Mai 1930 schrieb Jünger:

Unser Gesellschaftsgefühl ist anarchisch. [...] Überall offenbart sich das Streben nach neuer Ordnung, nach Schaffung neuer, im besten Sinne männlicher Werte. Eine Evolution aber ist unmöglich! Nur die kommende, die mit zwingender Gewalt kommende Revolution kann Besserung bringen. [...] Erst aus den Tiefpunkten kulturpolitischer Falschwirtschaft wird sich – gemäß des ehernen Gesetzes der Weltgeschichte – bei uns der Aufstieg vollziehen! (S. 583)

Bestimmt man die >Konservative Revolution< als den radikalen Versuch, das, was traditionell in Deutschland Konservatismus genannt wird, unter den Bedingungen einer antikonservativen Zeit wieder zu beleben, so kann Jünger nach 1926 eigentlich nicht mehr zur >Konservativen Revolution< gezählt werden.

Für Mohler, der einen ungeschichtlichen, eher anthropologischen Konservatismusbegriff zu Grunde legt, bietet Jüngers Denken um 1929 jedoch beinahe den Idealtyp der >Konservativen Revolution<. In einer Hinsicht bleibt jedoch eine Spannung. Die Absage an jede geschichtliche Überlieferung bedeutet auch eine Absage an Geschichtsphilosophie. Jünger bleibt jedoch durch seinen Hang zur Idee dem geschichtsphilosophischen Denken in einem wesentlichen Punkt verhaftet. 44

Die Edition

Zum Schluß noch einige Bemerkungen zu der von Sven Berggötz besorgten Edition. Leider haben sich in die Texte Jüngers einige Fehler eingeschlichen. Bei der Edition eines Klassikers ist dies besonders ärgerlich.

An einigen Stellen störte sich Berggötz an Jüngers Grammatik und griff in den Text ein. Einen Autor vom Format Jüngers bei der Bildung eines Genitivs zu korrigieren, ist eigentlich überflüssig.

Einige der Texteingriffe sind jedoch unbegreiflich. Sie zeigen, wie fremd dem Herausgeber das Denken Jüngers geblieben ist. Natürlich meint Jünger in der folgend angeführten Passage "das Arbeiten der Idee" und nicht ein "Arbeiten an einer Idee". Ideen sind für Jünger überpersönliche Mächte: "Denn was jetzt in allen Völkern vor sich geht, ist das Arbeiten [an] einer universalen Idee" (S. 262).

Weshalb es in der folgenden Passage "Tugend" heißen soll, wie Berggötz in seinem Kommentar vermutet (S. 770), ist ebenfalls nicht einzusehen: "Es bedürfte dieser Aufforderung nicht, denn ich betrachte mich überall als Mitkämpfer, wo man mit jener stillen Entschiedenheit, in der ich die für unsere Zeit notwendigste Jugend [sic] erblicke, an der Rüstung ist" (S. 449f.). Unverständlich ist auch, weshalb die wenigen Fußnoten Jüngers sich nicht in den Texten Jüngers, sondern in den Kommentaren finden.

In den Kommentaren finden sich zwar viele interessante und hilfreiche Erläuterungen, einige Kommentare provozieren jedoch Kritik. In einem Kommentar zum "Fundamentalsatze des Descartes" (S. 503) heißt es, das "ich denke, also bin ich" sei "der erste absolut gewisse Grundsatz, mit dem Descartes die Wende der neuzeitlichen Philosophie zum Sein begründete" (S. 710). Einmal ganz abgesehen davon, daß ein Kommentar zu Descartes' "Fundamentalsatz" vezichtbar wäre: Mit gleichem Recht könnte es auch heißen, der Satz begründe die Wende zum Bewußtsein.

Ein anderes Beispiel: Eine Bemerkung Jüngers über Keyserlings Reisetagebuch eines Philosophen (S. 160) kommentiert Berggötz mit dem Hinweis, Thomas Mann hätte das Buch für die Frankfurter Zeitung rezensieren sollen. Nun weiß der Leser, daß sich Berggötz auch für Thomas Mann interessiert. Für das Verständnis von Jüngers Text ist dieser Kommentar unerheblich.

Viele eindeutige Anspielungen und Zitate blieben hingegen unkommentiert. Nicht wo sich Goethes Wendung "alles Vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis" findet, sondern wo Rathenau gesagt hat, daß die Weltgeschichte ihren Sinn verloren hätte, "wenn die Repräsentanten des Reiches als Sieger durch das Brandenburger Tor in die Hauptstadt eingezogen wären" (S. 575), möchte man gerne erfahren.

Matthias Schloßberger, M.A.

Universität Potsdam

Institut für Philosophie

Praktische Philosophie / Philosophische Anthropologie

Am Neuen Palais, Haus 11

D - 14469 Potsdam

Homepage

Copyright © by the author. All rights reserved.

This work may be copied for non-profit educational use if proper credit is given to the author and IASLonline.

For other permission, please contact IASLonline.

Diese Rezension wurde betreut von unserem Fachreferenten PD Dr. Alf Christophersen. Sie finden den Text auch angezeigt im Portal Lirez – Literaturwissenschaftliche Rezensionen.

So what exactly is fascism? This question, Gottfried insists, “has sometimes divided scholars and has been asked repeatedly ever since Mussolini’s followers marched on Rome in October 1922.” Gottfried presents several adjectives, mostly gleaned from the work of others, to describe fascism: reactionary, counterrevolutionary, collectivist, authoritarian, corporatist, nationalist, modernizing, and protectionist. These words combine to form a unified sense of what fascism is, although we may never settle on a fixed definition because fascism has been linked to movements with various distinct characteristics. For instance, some fascists were Christian (e.g., the Austrian clerics or the Spanish Falange) and some were anti-Christian (e.g., the Nazis). There may be some truth to the “current equation of fascism with what is reactionary, atavistic, and ethnically exclusive,” Gottfried acknowledges, but that is only part of the story.

So what exactly is fascism? This question, Gottfried insists, “has sometimes divided scholars and has been asked repeatedly ever since Mussolini’s followers marched on Rome in October 1922.” Gottfried presents several adjectives, mostly gleaned from the work of others, to describe fascism: reactionary, counterrevolutionary, collectivist, authoritarian, corporatist, nationalist, modernizing, and protectionist. These words combine to form a unified sense of what fascism is, although we may never settle on a fixed definition because fascism has been linked to movements with various distinct characteristics. For instance, some fascists were Christian (e.g., the Austrian clerics or the Spanish Falange) and some were anti-Christian (e.g., the Nazis). There may be some truth to the “current equation of fascism with what is reactionary, atavistic, and ethnically exclusive,” Gottfried acknowledges, but that is only part of the story.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’idéologie, domaine des idées, est la chasse gardée des intellos. Ceux-ci alimentent les politiciens ignares par des constructions abstraites, vendables aux masses, autrement dit une bouillie où l’on se pose surtout ‘contre’ et rarement ‘pour’. « Il y a les préjugés de tout ce monde ‘affranchi’. Il y a là une masse de plus en plus figée, de plus en plus lourde, de plus en plus écrasante. On est contre ceci, contre cela, ce qui fait qu’on est pour le néant qui s’insinue partout. Et tout cela n’est que faible vantardise » p.1131. Yaka…

L’idéologie, domaine des idées, est la chasse gardée des intellos. Ceux-ci alimentent les politiciens ignares par des constructions abstraites, vendables aux masses, autrement dit une bouillie où l’on se pose surtout ‘contre’ et rarement ‘pour’. « Il y a les préjugés de tout ce monde ‘affranchi’. Il y a là une masse de plus en plus figée, de plus en plus lourde, de plus en plus écrasante. On est contre ceci, contre cela, ce qui fait qu’on est pour le néant qui s’insinue partout. Et tout cela n’est que faible vantardise » p.1131. Yaka… On parle aujourd’hui volontiers dans les meetings de 1789, de 1848, voire de 1871. Mais la grande politique va bien au-delà, de Gaulle la reprendra à son compte et Mitterrand en jouera. Marine Le Pen encense Jeanne d’Arc (comme Drieu) et Mélenchon tente de récupérer les grandes heures populaires, mais avec le regard myope du démagogue arrêté à 1793. Or « il y avait eu la raison française, ce jaillissement passionné, orgueilleux, furieux du XIIè siècle des épopées, des cathédrales, des philosophies chrétiennes, de la sculpture, des vitraux, des enluminures, des croisades. Les Français avaient été des soldats, des moines, des architectes, des peintres, des poètes, des maris et des pères. Ils avaient fait des enfants, ils avaient construit, ils avaient tué, ils s’étaient fait tuer. Ils s’étaient sacrifiés et ils avaient sacrifié. Maintenant, cela finissait. Ici, et en Europe. ‘Le peuple de Descartes’. Mais Descartes encore embrassait la foi et la raison. Maintenant, qu’était ce rationalisme qui se réclamait de lui ? Une sentimentalité étroite et radotante, toute repliée sur l’imitation rabougrie de l’ancienne courbe créatrice, petite tige fanée » p.1221. Marc Bloch, qui n’était pas fasciste puisque juif, historien et résistant, était d’accord avec Drieu pour accoler Jeanne d’Arc à 1789, le suffrage universel au sacre de Reims. Pour lui, tout ça était la France : sa mystique. Ce qui meut la grande politique et ce qui fait la différence entre la gestion d’un conseil général et la gestion d’un pays.

On parle aujourd’hui volontiers dans les meetings de 1789, de 1848, voire de 1871. Mais la grande politique va bien au-delà, de Gaulle la reprendra à son compte et Mitterrand en jouera. Marine Le Pen encense Jeanne d’Arc (comme Drieu) et Mélenchon tente de récupérer les grandes heures populaires, mais avec le regard myope du démagogue arrêté à 1793. Or « il y avait eu la raison française, ce jaillissement passionné, orgueilleux, furieux du XIIè siècle des épopées, des cathédrales, des philosophies chrétiennes, de la sculpture, des vitraux, des enluminures, des croisades. Les Français avaient été des soldats, des moines, des architectes, des peintres, des poètes, des maris et des pères. Ils avaient fait des enfants, ils avaient construit, ils avaient tué, ils s’étaient fait tuer. Ils s’étaient sacrifiés et ils avaient sacrifié. Maintenant, cela finissait. Ici, et en Europe. ‘Le peuple de Descartes’. Mais Descartes encore embrassait la foi et la raison. Maintenant, qu’était ce rationalisme qui se réclamait de lui ? Une sentimentalité étroite et radotante, toute repliée sur l’imitation rabougrie de l’ancienne courbe créatrice, petite tige fanée » p.1221. Marc Bloch, qui n’était pas fasciste puisque juif, historien et résistant, était d’accord avec Drieu pour accoler Jeanne d’Arc à 1789, le suffrage universel au sacre de Reims. Pour lui, tout ça était la France : sa mystique. Ce qui meut la grande politique et ce qui fait la différence entre la gestion d’un conseil général et la gestion d’un pays. Mais la démocratie parlementaire a montré que la mystique pouvait surgir, comme sous Churchill, de Gaulle, Kennedy, Obama. Sauf que le parlementarisme reprend ses droits et assure la distance nécessaire entre l’individu et la masse nationale. Délibérations, pluralisme et État de droit sont les processus et les garde-fous de nos démocraties. Ils permettent l’équilibre entre la vie personnelle de chacun (libre d’aller à ses affaires) et la vie collective de l’État-nation (en charge des fonctions régaliennes de la justice, la défense et les infrastructures). Notre système requiert des administrateurs rationnels plus que des leaders charismatiques, malgré le culte du chef réintroduit par la Vè République.

Mais la démocratie parlementaire a montré que la mystique pouvait surgir, comme sous Churchill, de Gaulle, Kennedy, Obama. Sauf que le parlementarisme reprend ses droits et assure la distance nécessaire entre l’individu et la masse nationale. Délibérations, pluralisme et État de droit sont les processus et les garde-fous de nos démocraties. Ils permettent l’équilibre entre la vie personnelle de chacun (libre d’aller à ses affaires) et la vie collective de l’État-nation (en charge des fonctions régaliennes de la justice, la défense et les infrastructures). Notre système requiert des administrateurs rationnels plus que des leaders charismatiques, malgré le culte du chef réintroduit par la Vè République.

En effet, il me paraît très important de replacer la révolution conservatrice allemande dans un contexte temporel plus vaste et plus profond, comme d’ailleurs Armin Mohler lui-même l’avait envisagé, suite à la publication des travaux de Zeev Sternhell sur la droite révolutionnaire française d’après 1870, qui représente une réaction musclée, une volonté de redresser la nation vaincue : après la défaite de 1918 et le Traité de Versailles de juin 1919, c’est ce modèle français qu’évoquait explicitement l’Alsacien Eduard Stadtler, un ultra-nationaliste allemand, bilingue, issu du Zentrum démocrate-chrétien, fondateur du Stahlhelm paramilitaire et compagnon de Moeller van den Bruck dans son combat métapolitique de 1918 à 1925. L’Allemagne devait susciter en son sein l’émergence d’un réseau de cercles intellectuels et politiques, d’associations diverses, de sociétés de pensée et de groupes paramilitaires pour redonner au Reich vaincu un statut de pleine souveraineté sur la scène européenne et internationale.

En effet, il me paraît très important de replacer la révolution conservatrice allemande dans un contexte temporel plus vaste et plus profond, comme d’ailleurs Armin Mohler lui-même l’avait envisagé, suite à la publication des travaux de Zeev Sternhell sur la droite révolutionnaire française d’après 1870, qui représente une réaction musclée, une volonté de redresser la nation vaincue : après la défaite de 1918 et le Traité de Versailles de juin 1919, c’est ce modèle français qu’évoquait explicitement l’Alsacien Eduard Stadtler, un ultra-nationaliste allemand, bilingue, issu du Zentrum démocrate-chrétien, fondateur du Stahlhelm paramilitaire et compagnon de Moeller van den Bruck dans son combat métapolitique de 1918 à 1925. L’Allemagne devait susciter en son sein l’émergence d’un réseau de cercles intellectuels et politiques, d’associations diverses, de sociétés de pensée et de groupes paramilitaires pour redonner au Reich vaincu un statut de pleine souveraineté sur la scène européenne et internationale.

A la fin du siècle, l’Europe, par le truchement de ces « sciences allemandes », dispose d’une masse de connaissances en tous domaines qui dépassent les petits mondes étriqués des politiques politiciennes, des rabâchages de la caste des juristes, des calculs mesquins du monde économique. Rien n’a changé sur ce plan. Quant à la révolution conservatrice proprement dite, qui veut débarrasser les sociétés européennes de toutes ces scories accumulées par avocats et financiers, politicards et spéculateurs, prêtres sans mystique et bourgeois égoïstes, elle démarre essentiellement par l’initiative que prend en 1896 l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs. Il cultivait l’ambition de proposer à la lecture et à la réflexion une formidable batterie d’idées innovantes capables, à terme, de modeler une société nouvelle, enclenchant de la sorte une révolution véritable qui ne suggère aucune table rase mais au contraire entend ré-enchanter les racines, étouffées sous les scories des conformismes. La même année, le jeune romantique Karl Fischer fonde le mouvement des Wandervögel, dont l’objectif est d’arracher la jeunesse à tous les conformismes et aussi de la sortir des sinistres quartiers surpeuplés des villes devenues tentaculaires suite à la révolution industrielle. Eugen Diederichs veut un socialisme non matérialiste, une religion nouvelle puisant dans la mémoire du peuple et renouant avec les mystiques médiévales (Maître Eckhart, Ruusbroec, Nicolas de Cues, etc.), une libéralisation sexuelle, un néo-romantisme inspiré par des sources allemandes, russes, flamandes ou scandinaves.

A la fin du siècle, l’Europe, par le truchement de ces « sciences allemandes », dispose d’une masse de connaissances en tous domaines qui dépassent les petits mondes étriqués des politiques politiciennes, des rabâchages de la caste des juristes, des calculs mesquins du monde économique. Rien n’a changé sur ce plan. Quant à la révolution conservatrice proprement dite, qui veut débarrasser les sociétés européennes de toutes ces scories accumulées par avocats et financiers, politicards et spéculateurs, prêtres sans mystique et bourgeois égoïstes, elle démarre essentiellement par l’initiative que prend en 1896 l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs. Il cultivait l’ambition de proposer à la lecture et à la réflexion une formidable batterie d’idées innovantes capables, à terme, de modeler une société nouvelle, enclenchant de la sorte une révolution véritable qui ne suggère aucune table rase mais au contraire entend ré-enchanter les racines, étouffées sous les scories des conformismes. La même année, le jeune romantique Karl Fischer fonde le mouvement des Wandervögel, dont l’objectif est d’arracher la jeunesse à tous les conformismes et aussi de la sortir des sinistres quartiers surpeuplés des villes devenues tentaculaires suite à la révolution industrielle. Eugen Diederichs veut un socialisme non matérialiste, une religion nouvelle puisant dans la mémoire du peuple et renouant avec les mystiques médiévales (Maître Eckhart, Ruusbroec, Nicolas de Cues, etc.), une libéralisation sexuelle, un néo-romantisme inspiré par des sources allemandes, russes, flamandes ou scandinaves.

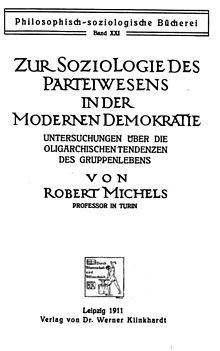

Il faut se rappeler que le rejet le mieux charpenté de la démocratie libérale et surtout de ses dérives partitocratiques ne provient pas d’un mouvement ou cénacle émanant d’une droite posée comme « conservatrice-révolutionnaire » mais d’une haute figure de la social-démocratie allemande et européenne, Roberto Michels, actif en Belgique, en Allemagne et en Italie avant 1914. Ici aussi, je ne fais pas d’anachronisme : à l’université en 1974, on nous conseillait la lecture de sa critique des oligarchies politiciennes (sociaux-démocrates compris) ; après une éclipse navrante de quelques décennies, je constate avec bonheur qu’une grande maison française, Gallimard-Folio, vient de rééditer sa Sociologie du parti dans la démocratie moderne (Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens), qui démontre avec une clarté inégalée les dérives dangereuses d’une démocratie partitocratique : coupure avec la base, oligarchisation, règne des « bonzes », compromis contraires aux promesses électorales et aux programmes, bref, les maux que tous sont bien contraints de constater aujourd’hui en Europe et ailleurs, en plus amplifiés ! Michels suggère des correctifs : référendum (démocratie directe), renonciation (aux modes de vie matérialistes et bourgeois, ascétisme de l’élite politique se voulant alternative), etc. Dans cet ouvrage fondamental des sciences politiques, Michels vise à dépasser tout ce qui fait le ronron d’un parti (et, partant, d’une vie politique nationale orchestrée autour du jeu répétitif des élections récurrentes d’un certain nombre de partis établis) et suggère des pistes pour échapper à ces enlisements ; elles annoncent les aspirations ultérieures des conservateurs-révolutionnaires (ou assimilés) d’après 1918 et surtout d’après Locarno, sans oublier les futurs non-conformistes français des années 30 et ceux qui, aujourd’hui, cherchent à sortir des impasses où nous ont fourvoyés les établis. Ces pistes insistent sur la nécessité d’avoir des élites politiques ascétiques, sur une virulence correctrice que Michels croyait déceler dans le syndicalisme révolutionnaire (et ses versions italiennes comme celles activées par Filippo Corridoni avant 1914 – Corridoni tombera au front en 1915), dans les idées activistes de Georges Sorel et dans certaines formes d’anarchisme hostiles aux hiérarchies figées. L’idée-clef est de traquer partout, dans les formes de représentation politique, les éléments négatifs qui figent, qui induisent des répétitions lesquelles annulent l’effervescence révolutionnaire ou la dynamique douce/naturelle du peuple, oblitèrent la spontanéité des masses (on y reviendra en mai 68 !). En ce sens, les idées de Michels, Corridoni et Sorel entendent conserver les potentialités vivantes du peuple qui, le cas échéant et quand nécessité fait loi, sont capables de faire éclore un mouvement révolutionnaire correcteur et éradicateur des fixismes répétitifs.

Il faut se rappeler que le rejet le mieux charpenté de la démocratie libérale et surtout de ses dérives partitocratiques ne provient pas d’un mouvement ou cénacle émanant d’une droite posée comme « conservatrice-révolutionnaire » mais d’une haute figure de la social-démocratie allemande et européenne, Roberto Michels, actif en Belgique, en Allemagne et en Italie avant 1914. Ici aussi, je ne fais pas d’anachronisme : à l’université en 1974, on nous conseillait la lecture de sa critique des oligarchies politiciennes (sociaux-démocrates compris) ; après une éclipse navrante de quelques décennies, je constate avec bonheur qu’une grande maison française, Gallimard-Folio, vient de rééditer sa Sociologie du parti dans la démocratie moderne (Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens), qui démontre avec une clarté inégalée les dérives dangereuses d’une démocratie partitocratique : coupure avec la base, oligarchisation, règne des « bonzes », compromis contraires aux promesses électorales et aux programmes, bref, les maux que tous sont bien contraints de constater aujourd’hui en Europe et ailleurs, en plus amplifiés ! Michels suggère des correctifs : référendum (démocratie directe), renonciation (aux modes de vie matérialistes et bourgeois, ascétisme de l’élite politique se voulant alternative), etc. Dans cet ouvrage fondamental des sciences politiques, Michels vise à dépasser tout ce qui fait le ronron d’un parti (et, partant, d’une vie politique nationale orchestrée autour du jeu répétitif des élections récurrentes d’un certain nombre de partis établis) et suggère des pistes pour échapper à ces enlisements ; elles annoncent les aspirations ultérieures des conservateurs-révolutionnaires (ou assimilés) d’après 1918 et surtout d’après Locarno, sans oublier les futurs non-conformistes français des années 30 et ceux qui, aujourd’hui, cherchent à sortir des impasses où nous ont fourvoyés les établis. Ces pistes insistent sur la nécessité d’avoir des élites politiques ascétiques, sur une virulence correctrice que Michels croyait déceler dans le syndicalisme révolutionnaire (et ses versions italiennes comme celles activées par Filippo Corridoni avant 1914 – Corridoni tombera au front en 1915), dans les idées activistes de Georges Sorel et dans certaines formes d’anarchisme hostiles aux hiérarchies figées. L’idée-clef est de traquer partout, dans les formes de représentation politique, les éléments négatifs qui figent, qui induisent des répétitions lesquelles annulent l’effervescence révolutionnaire ou la dynamique douce/naturelle du peuple, oblitèrent la spontanéité des masses (on y reviendra en mai 68 !). En ce sens, les idées de Michels, Corridoni et Sorel entendent conserver les potentialités vivantes du peuple qui, le cas échéant et quand nécessité fait loi, sont capables de faire éclore un mouvement révolutionnaire correcteur et éradicateur des fixismes répétitifs.

Reste aussi un autre problème que l’époque et ses avant-gardes politiques et littéraires ont tenté de résoudre dans la pétulance et l’intempérance : celui de la vitesse. Chez les futuristes, c’est clair, surtout dans certaines de leurs plus belles œuvres picturales, la vitesse est l’ivresse du monde, le mode exaltant qui, maîtrisé ou chevauché, permet d’échapper justement aux fixismes, au « passatismo ». A gauche aussi, la révolution a pour but de réaliser vite les aspirations populaires. Le prolétariat révolutionnaire des bolcheviques, une fois au pouvoir, maîtrise les machines et les rapidités qu’elles procurent. Le conseillisme bavarois, quant à lui, ne souhaitait pas effacer les spontanéités vitales de la population. Le fascisme de Mussolini, venu du socialisme et du syndicalisme sorélien et corrodinien, ne l’oublions jamais, entend réaliser en six heures ce que la démocratie parlementaire et palabrante (et donc lente, hyper-lente) fait en six ans. Les réactionnaires, que les futuristes ou les bolcheviques jugeront « passéistes », rappelaient que la prise de décision du monarque ou du petit nombre dans les anciens régimes était plus rapide que celle des parlements (d’où la présence récurrente de figures de la contre-révolution française dans les démarches intellectuelles d’Ernst Jünger, fussent-elles les plus maximalistes avant 1925). Un système politique cohérent, pour les avant-gardes des années 20, doit donc pouvoir décider rapidement, à la vitesse des nouvelles machines, des bolides Bugatti ou Mercedes, des avions des pionniers de l’air, des vedettes rapides des nouvelles forces navales (d’Annunzio). Une force politique nouvelle, démocratique ou non (Fiume est une démocratie avant-gardiste !), doit être décisionnaire et rapide, donc jeune. Si elle est parlementaire et palabrante, elle est lente donc vieille et cette sénilité pétrifiée mérite d’être jetée bas. La double idée de décision et de rapidité d’exécution est évidemment présente dans le nationalisme soldatique et explique pourquoi le coup de force est considéré comme plus efficace et plus propre que les palabres parlementaires. Elle apparait ensuite dans la théorie politique plus élaborée et plus juridique de Carl Schmitt, qui rejette le normativisme (comme étant un système de règles figées finalement incapacitantes quand le danger guette la Cité, où la « lex », par sa lourde présence, sape l’action du « rex ») et le positivisme juridique, trop technique et inattentif aux valeurs pérennes. Schmitt, décisionniste, prône évidemment le décisionnisme, dont il est le représentant le plus emblématique, et insiste sur la nécessité permanente d’agir au sein d’ordres concrets, réellement existants, hérités, légués par l’histoire et les traditions politiques de la Cité (ce qui implique le rejet de toute volonté de créer un « Etat mondial »).